The Abduction of Persephone is one of the most enduring stories from Greek mythology. At first glance it seems like a simple tale of a girl taken by the king of the underworld, but it is also a layered meditation on seasons, agriculture, power, and the bonds between mothers and daughters. Explaining it in a way that speaks to high school students means looking at both the plot and the deeper meanings the myth has carried for centuries.

Who are the key players? Persephone, also called Kore (the Maiden), is the daughter of Demeter, goddess of grain and harvest, and Zeus, king of the gods. Her mother embodies the earth’s fertility and the life-giving force of agriculture. Hades, the god of the Underworld, rules over the realm of the dead. Though he is often portrayed as fearsome, his relationship with Persephone is complicated—part longing, part political arrangement among the gods. Demeter is devoted to her daughter and to people who depend on crops for survival. The myth (as most people know it) explains a seasonal pattern: when Persephone is away, Demeter grieves, and the earth withers; when Persephone returns, life returns to the fields.

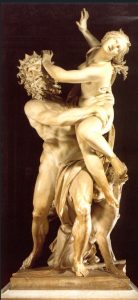

The moment of abduction can be told in a few vivid lines that recur in many versions. Persephone is said to be in a field or garden, often gathering flowers, when a sudden chariot—pulled by terrifying black horses—appears. Hades rises from the earth andwooed or seized her, depending on the telling, and she is carried down into the Underworld. In some images she is lured by a single, magical flower; in others she is seized as the ground shakes beneath her. The important point is that Persephone is taken from the world of the living into the realm of the dead, a move that forces Demeter to confront a devastating loss.

Demeter’s response is intense and personal, which is part of why the myth resonates. She travels the earth in search of her daughter, abandoning her duties as a goddess of fertility. She disguises herself and begs mortals for news of Persephone, refusing to let crops grow while the world remains in despair. The earth becomes barren; famine threatens, and people begin to fear the loss of seasonal food. This is not merely a tale about a daughter’s disappearance; it is a narrative about the fragile link between the divine world and human survival. The gods’ quarrels have real consequences for farmers, for cities, and for children who depend on the harvest for survival.

The gods eventually intervene. Helios, the sun, is one of the few who sees through the confusion and tells Demeter the truth: Persephone has been taken to the Underworld, and Zeus has permitted it, though often with the intention of balancing Hades’ needs with the world above. Hermes, the swift messenger of the gods, is sent to guide Persephone back from the land of shadows. In most tellings, Persephone emerges, and a compromise is reached: she will spend part of each year with Hades in the Underworld and part of each year with Demeter on earth. The exact proportion is most often described as half the year, commonly interpreted as six months, though some versions speak more generally of a portion of the year.

The moment Persephone returns is celebrated as springtime in many Greek stories. Demeter’s joy at reunion with her daughter marks the renewal of growth and flowering in nature. Conversely, when Persephone returns to the Underworld, Demeter’s sorrow returns as well, and winter settles over the earth. This cyclical pattern—loss and reunion, famine and bounty—gives the myth its enduring scientific and symbolic power. It is often read as an ancient explanation for the seasons: the earth sleeps through winter as a goddess grieves, then awakens with Persephone’s return each spring.

Beyond agriculture, the Persephone myth is rich with themes that invite a range of interpretations. It is about change and transformation: Persephone is no longer the pure maiden Kore when she returns; she becomes Queen of the Underworld, a figure who embodies both death and fertility. The shift from daughter to wife to queen mirrors the cycles of life itself. The mother-daughter bond between Demeter and Persephone is central as well—one that moves from dependence and longing to a more complicated form of partnership in governing the balance between life and death.

The myth also raises questions about consent, power, and the autonomy of women in a world ruled by gods. Some modern readers emphasize that Persephone’s act of being taken—whether framed as abduction or as a binding marriage—sees her agency constrained within a male-dominated cosmos. Others stress Persephone’s own authority and the way her presence as queen of the Underworld shapes the order of both realms. These discussions show how a seemingly ancient story can prompt fresh thinking about gender, power, and responsibility.

Culturally, the Persephone story had a major impact in the ancient world. It is tightly linked to the Eleusinian Mysteries, secret religious rites that celebrated Demeter and Persephone and promised initiates a favorable fate in the afterlife. The myth provided a sacred framework for understanding life, death, and rebirth, and it helped explain why people would participate in agricultural rituals that ensured good harvests. Later, the Roman adaptation transformed Persephone into Proserpina, and the story continued to influence art, poetry, and philosophy. In Renaissance and modern art, Persephone has appeared in paintings and literature as a symbol of seasonal renewal and the tension between light and darkness. Her journey has been reimagined in numerous works that explore themes of loss, memory, and resilience.

There are several ways to connect this myth to this article. One could frame it as a case study in how ancient cultures explained natural phenomena—why winter comes, why crops fail, and how people found meaning in those cycles. Another angle is to examine the role of the divine family in Greek myth and how familial relationships shape outcomes in the mortal world. A literary approach could compare Homeric Hymn to Demeter with later retellings, highlighting how language, imagery, and emphasis shift across eras. A third approach looks at gender and power: how Persephone’s absence affects Demeter’s powers, how agency is negotiated, and what the myth suggests about the responsibilities that come with leadership in a world governed by gods.

In conclusion, the Abduction of Persephone is more than an adventure tale. It is a foundational myth that ties together themes of seasonal change, agricultural survival, divine politics, and the complex dynamics between mothers and daughters. It invites readers to think about how struggles in the celestial realm ripple through the human world, influencing daily life, rituals, and the way cultures understand time itself. Whether read as a story about the persistence of life amid loss, the cycles of the earth, or a meditation on power and agency, Persephone’s journey remains a powerful lens through which to view the world’s rhythms and the human longing for renewal.